I’ve driven by this sign several hundred times over the last few decades. I’ve stopped to make pictures of it a few times as have countless others undoubtedly. I made this picture one Sunday a few weeks ago with a new-to-me camera after a long, but productive day of looking and listening and turning around and going back.

When I got the film and scans back, I settled in on this picture and thought about the times I’d seen it in the early morning fog, the driving rain, and when it was nearly invisible, blanketed in snow. I knew there was a name and phone number on the sign, but never paid it much mind.

Looking at the picture again yesterday, I picked up the phone and called the number. A man’s voice sang hello on the other end. “Mr. Bell?” I asked. It was, he said. I told him who I was and that I was calling to ask about the sign on US 119. For the next 10 minutes, Mr. Ed Bell, who is “88 and a half” proceeded to tell me about himself, his sign ministry, and about how wonderful it was to receive a phone call out of the blue about one of his signs.

He reckons this particular sign was put up about 20 years ago. If you’ll notice on the far left, you’ll see the initials “H.S.” Mr. Bell told me he dedicated the sign to his good friend Harlena Shepherd, who gave him $25 to help make the sign all those years ago.

He told me I could call him anytime. He said he was going to pray for me as soon as we got off the phone. “You’ve made my day. Thank you, young man,” he said as we hung up. Thank you, Mr. Bell.

Heart in Place: Kwasi Boyd-Bouldin

You might be wondering why you’re looking at pictures of Los Angeles on a blog that deal primarily with work from Appalachia. From my desk in Charleston, West Virginia, Los Angeles is more than 2,300 miles away, but there is a proximity of heart for place I find in Kwasi Boyd-Bouldin’s photographs that I’d like to share.

I first learned of Boyd-Bouldin’s work via Twitter, though I can’t remember exactly who shared it. I scrolled through some of his images online and was drawn in by his straightforward manner of looking. His compositions suggested an eye of someone looking beyond the surface and beyond the stereotype of place. This is not the Los Angeles you’ve often been shown.

After several months of following Boyd-Bouldin’s work on Twitter, and later Instagram, it occurred to me that he is looking at his corner of Los Angeles in a very similar way I’m making work in West Virginia and Appalachia. Despite the geographical differences, there is a common thread of love for place, a desire to show a more realistic portrayal of that place through critical looking and thinking, and to document the impact of the physical changes in the landscape of one’s home.

For all the things I detest about social media, every now and again, there are redeeming qualities. Had it not been for social media, I might have never known about Boyd-Bouldin’s work. I might have never had the chance to reach out to him to tell him how much I appreciate what he’s doing and why he’s doing it. I might never have had the chance to ask him about his work and to share some of that work here.

Boyd-Bouldin’s work is becoming more widely visible. In February of last year, he was included in TIME’s 12 African American Photographers You Should Follow Right Now and in November of last year, the New York Times LENS blog featured some of his photographs and a brief interview. One of the things he said in that piece illuminated a foundational element in the work he makes and made me think about the work I make: “In part, he says, the project is his intention to document a vanishing L.A. Few who live outside it even know it exists. He wants “to present a portrait of the city that reflects the lives of people who live in Los Angeles, as opposed to the glossy fictional version that dominates the mainstream narrative.” Just substitute Los Angeles with Appalachia or West Virginia or Kentucky.

In his series The Displacement Engine, in which he provides much needed critical thinking and viewing on the issue of gentrification, he writes, "The effort to push vulnerable populations to the margins may seem to be organic but it is often an organized campaign. Perpetual, neighborhood wide rent increases coupled with a total sustained lack of local infrastructure (grocery stores, good public schools, etc...) are the ingredients needed to initiate the desired effect." In West Virginia it isn't the same type of gentrification but it is systematic erasure. Apply this lens to look at the organized campaign of the coal industry to keep an already vulnerable population marginalized. In Mingo County, West Virginia, there isn't a single grocery store in the entire county. Likewise, four of the county's five high schools (Burch, Gilbert, Matewan, and Williamson) closed their doors in 2011 before consolidating into one school, Mingo Central, which is built on a reclaimed surface mine site.

I trust you'll enjoy Boyd-Bouldin's work and his thoughtful approach to place. Scroll through for our brief conversation, including a list of photographers he recommends following. You can see more of Boyd-Bouldin’s work at his website Kwasi Boyd-Bouldin and The Los Angeles Recordings. You can also follow him on Instagram and Twitter.

Roger May: Can you talk about the importance of photographing the place you’re from and how that informs your pictures?

Kwasi Boyd-Bouldin: Most people’s idea of what life is like in LA (and Hollywood specifically) is completely based in fantasy. I didn’t feel that the city I grew up in was being accurately represented in the media so I started documenting things from my perspective. It’s always been my goal to depict what Los Angeles looks and feels like from the street level. I think everyone should photograph their neighborhood.

RM: How about the importance of film? How and when did you begin to incorporate film (and digital) into your work?

KBB: My relationship with film photography started out of necessity, it was the only affordable medium when I started to get serious about photography. Over the years I stuck with it because it became the easiest way to get consistent results. It forces me to incorporate the element of time into my workflow and that is something that I apply to all of my photography regardless of platform. I’ve gone back and forth over the years but recently I have shifted back to a digital workflow (Fuji X).

RM: Your work speaks to me on a number of levels, but I’m particularly interested in your relationship to place and how you work to show the human interaction or imprint on the landscape. What is it about the landscape you feel compelled to document?

KBB: I’m drawn to photographing the urban landscape because of an interest in depicting and navigating large systems. Los Angeles is a knot of interlocking cultures, neighborhoods, and influences and I’ve always been inspired by how everything intersects. And for me, the landscape is the universal element that connects all of these different components. Everyone leaves their mark in one way or another and by stepping back you can see how all of those marks look collectively. That perspective is what’s missing from mainstream depictions of L.A. (and most other places) so that’s what I have focused on with my work.

RM: Can you tell me a little bit about who and what inspires you? Do you care to share what you’re reading or listening to right now?

KBB: I have a wide range of creative influences ranging from a lifelong addiction to Anime and science fiction to random conversations to people I meet on the street. In the realm of photography I’m influenced by Jamel Shabazz, Gordon Parks, Stephen Shore, William Eggleston, Latoya Ruby Frazier, Thomas Struth, and far too many more to list.

My father played the flute and the xylophone and my two older brothers were in a semi-famous old school rap group called 7A3 so I have always been surrounded by music. As a result I listen to a bit of everything, my current rotation includes Kendrick Lamar, Thundercat, MF Doom, Kamasi Washington, Little Dragon, Flying Lotus, Jay Z, Dabrye, Prhyme, Madlib, and a ton of other artists I’ve forgotten.

RM: The issue of gentrification is something many living in towns and cities are becoming more and more aware of. How do you see photography holding space for that conversation and the intersection of art/documentary and socioeconomics/politics?

KBB: I think that documenting neighborhoods as they exist currently and how they are being transformed is critical. Photography can be a vital part of that conversation but more people from the areas that are being gentrified need to be given the platform to share their stories. It really comes down to which perspectives are valued and why some interpretations are prioritized above others. Using photography to contextualize the lives and surroundings of the people affected is just the start, there needs to be a conversation about how neighborhoods can be revitalized without forcing people out of them.

RM: Who are other photographers folks should be paying attention to right now?

KBB: I think that we’re in the midst of a golden age in photography and thanks to platforms like Instagram you can come across a lot of incredible work you would miss otherwise. I think the following people are doing amazing things: Luis Torres, Erwin Recinos, Idris Solomon, Sean Maung, Michael Santiago, Scott Hurst, Aaron Turner, Gioncarlo Valentine, Jon Henry, Wendel White, and Nadia Huggins.

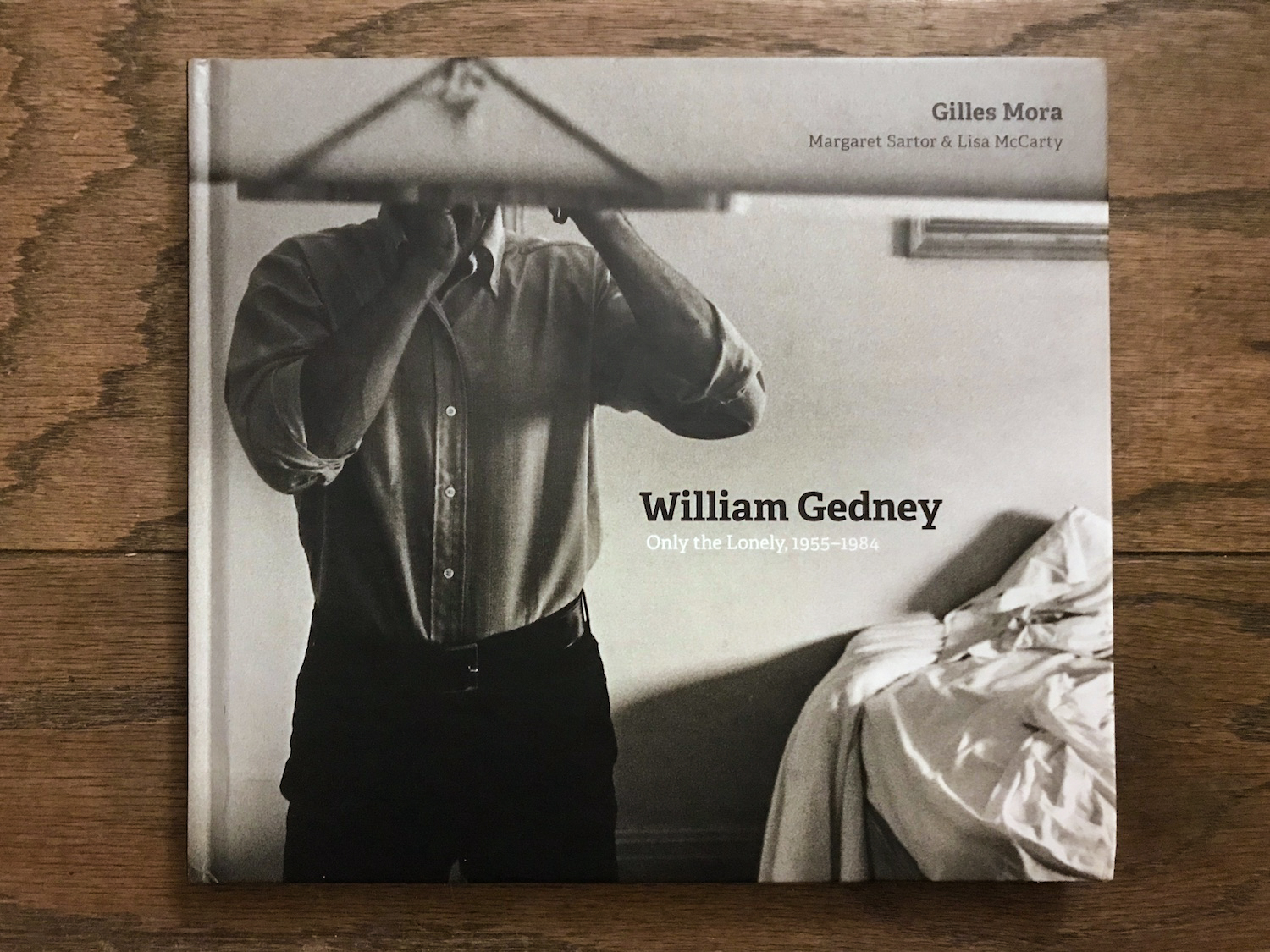

Review - William Gedney: Only the Lonely, 1955-1984

Hardcover | 10.5 x 9.5 inches | 160 pages | 160 duotone photographs | University of Texas Press, 2017 | Edited by Gilles Mora, Margaret Sartor, and Lisa McCarty

William Gedney’s work was once described as quiet poetry. I can’t think of a finer description of the photographer I’ve never met, but whose work has had a profound impact on my development as a photographer and understanding of photography in all its imperfections and limitations. Intimate is another word often used to describe his work, and although it truly is intimate, I worry that it has become something of a softball descriptor of work that is deeply complex and difficult to categorize. Only the Lonely provides us with a deeper dive into the expansive work of William Gedney. There are three distinct pieces of writing by the editors: “William Gedney, So Similar, So Different: Alone are the Lonely” (Gilles Mora), “Short Distances and Definite Places” (Margaret Sartor), and “Intimate Gestures: Handmade Books by William Gedney” (Lisa McCarty). The book is divided into eight sections of photographs: The Farm, 1955-1959, Brooklyn, 1955-1979, Kentucky, 1964, 1972, United States, 1964-1972, San Francisco, 1965-1967, India, 1969-1971 and 1980, Europe, 1974, and Gay Pride Parades, 1975-1983.

Only the Lonely, is the most recent significant work of this little known photographer. After his death in 1989, Gedney left the responsibility of his archive to Lee Friedlander, who has published dozens of books of his own work and is still actively making books, yet Gedney never lived to see his work in book form. Sean O’Hagan, who writes about photography for the Guardian, called Gedney a “pioneer of immersive documentary.” There has been somewhat of a resurgence in the work of William Gedney, for which I’m incredibly thankful. In 2013, photographer Alec Soth published Iris Garden, a beautiful book of Gedney’s pictures combined with the writing of John Cage (now out of print). Before that, only one other book had been published dedicated solely to the work of William Gedney. In 1993, Duke University became the repository for 51.3 linear feet of Gedney’s work. Margaret Sartor, a photographer, writer, and teacher at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke, was approached by the library and asked to put together an exhibit of Gedney’s work. In 2000, Sartor and Geoff Dyer coedited What Was True: The Photographs and Notebooks of William Gedney (which quickly sold out and is also out of print).

William Gayle Gedney died on June 23, 1989 at the age 56. In his lifetime, he was awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship for photography (1966-67), a Fulbright Fellowship for photography in India (1969-71), a National Endowment for the Arts grant in photography (1975-76), and several other grants and fellowships. He had a show at the New York Museum of Modern Art (1968-69) as well as more than a dozen other exhibitions. I wrote about my desire for seeing Gedney’s Kentucky work come to fruition in book form exactly as he intended here.

In her essay “Short Distances and Definite Places,” Sartor writes of Gedney, “People trusted him. Moreover they trusted how he saw them.” This gets at the very heart of documentary and place-based work for me. It isn't enough to just earn the trust of folks who let you into their lives, although it is a critical and foundational step. Would that all of us in our documentary practice earn the trust of people to the extent that they trust how we see them. What a beautiful relationship to strive for and what a beautiful book to have as a reminder of its possibility.

The Virtue of the Long View

On the north side of the King Coal Highway in Mingo County, West Virginia, I found this stretch road. I thought it odd that the road went from dirt and gravel to coal for about a hundred yards and back again to dirt and gravel. After several minutes of breathing in the air, listening to the birds rustle around me, I raised my camera. That's when it occurred to me. I was standing in a place I wasn't supposed to be in. I wasn't trespassing, mind you, but rather I was standing on a reclaimed surface mine site in an area that had been blasted away to get at the coal underneath all except for that on which I now stood. I was photographing what was never intended to be seen, to be reveled in. I often think about ways in which photography has led me to places and people that I might not have otherwise encountered and places I might've never seen even in my home county.

There are so many known things in the world. How are they known? Are they known simply because we read about them, were taught about them in school? How many things that we truly know were learned by experience? The type of knowing and experience that you simply can’t escape, don’t want to escape. To truly know and experience place. To be from a place and of a place, to hold that place dear despite all its imperfections and shortcomings. I think I try to make pictures here because I need to make sense of this (mountaintop removal), to find some sort of order. The scale of the devastation is too large to comprehend sometimes. By slowing down and looking for any form of beauty or mystery, perhaps that makes it a little more bearable.

I keep coming back to the King Coal Highway knowing that I both appreciate it and despise it. I appreciate the views it provides, but despise the toll it has taken on the communities below. I despise the greed it represents. I resent all that was taken and will never be returned. Over and over again, I come back to walk and drive and look and think.

In the introduction to Paul Kwilecki's testament to home, One Place, Tom Rankin describes a note in Kwilecki's office from Richard Nelson’s The Island Within: “There may be more to learn by climbing the same mountain a hundred times than by climbing a hundred different mountains.”

I reckon.