“Is this still a red and blue world? I see it as dark as night. Not that it is obscure; rather, it’s opaque.” Eudora Welty, On Writing, 1949.

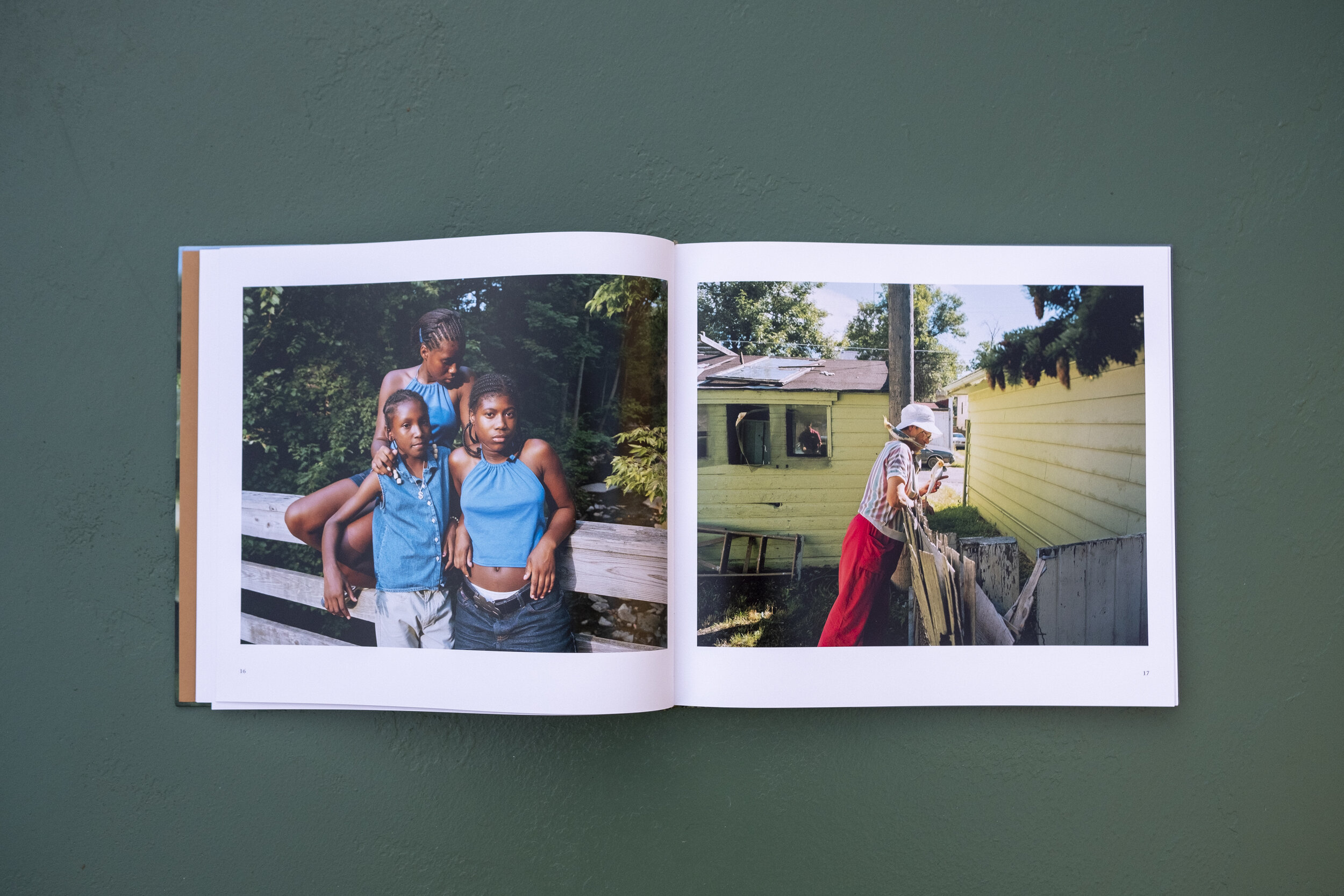

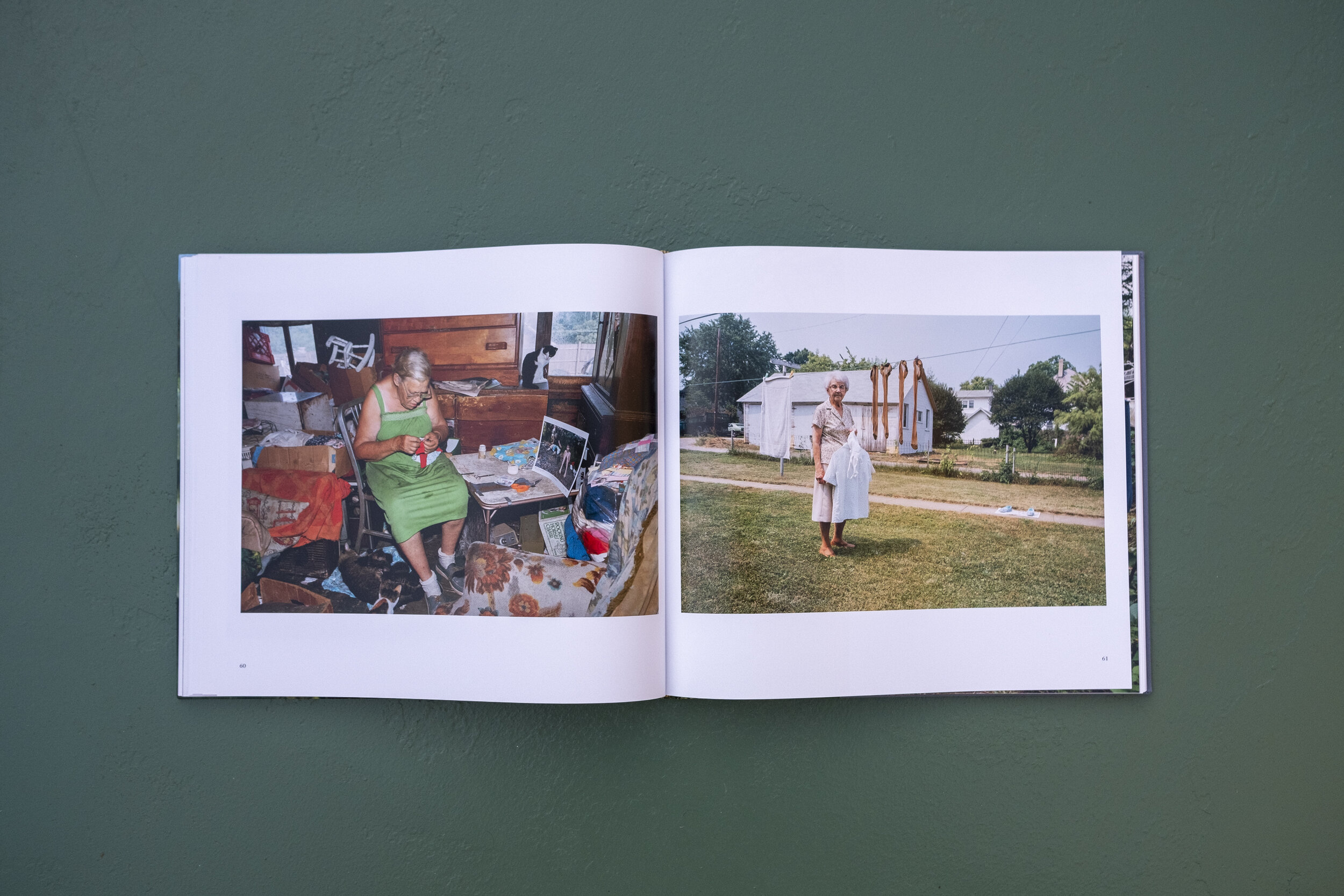

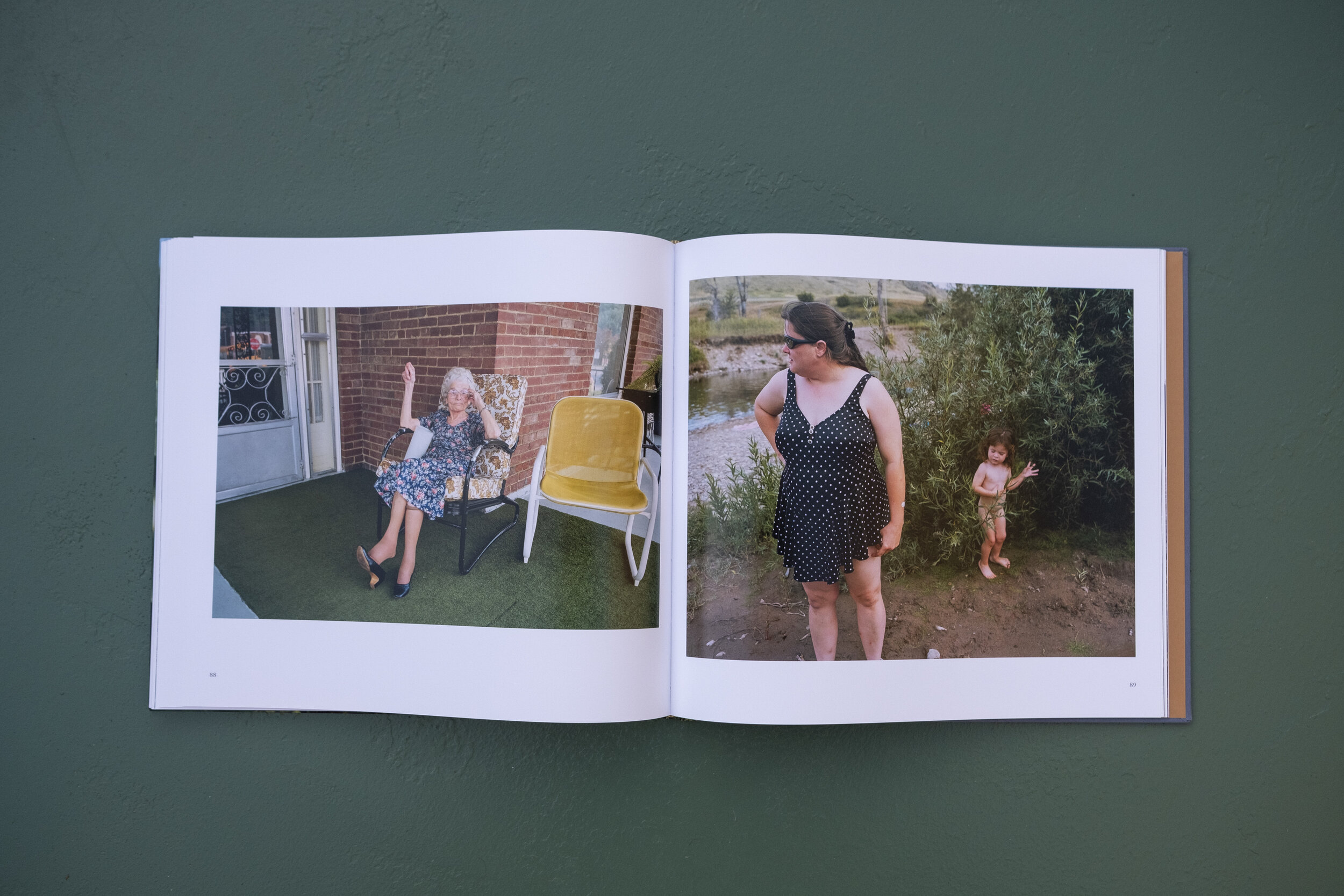

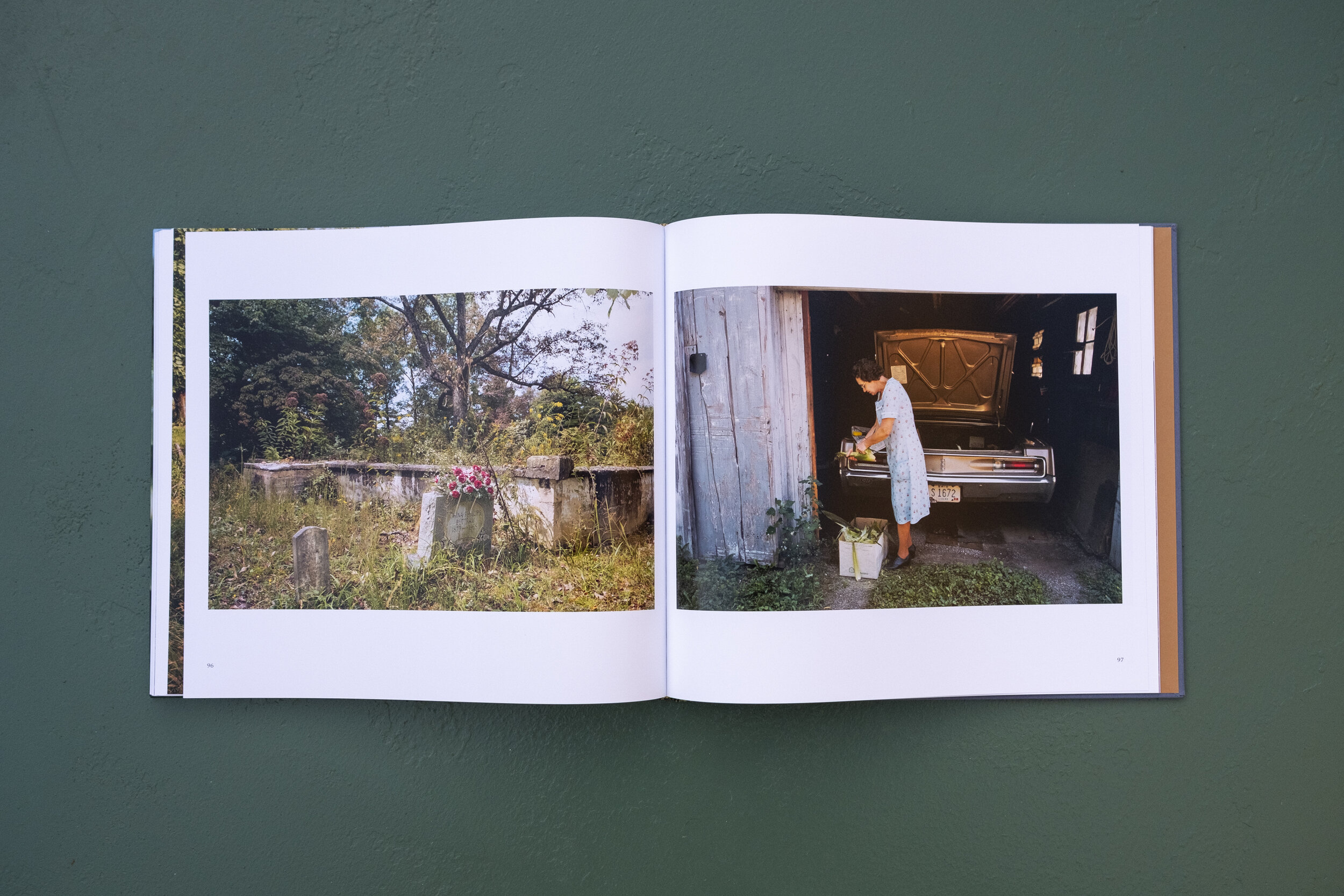

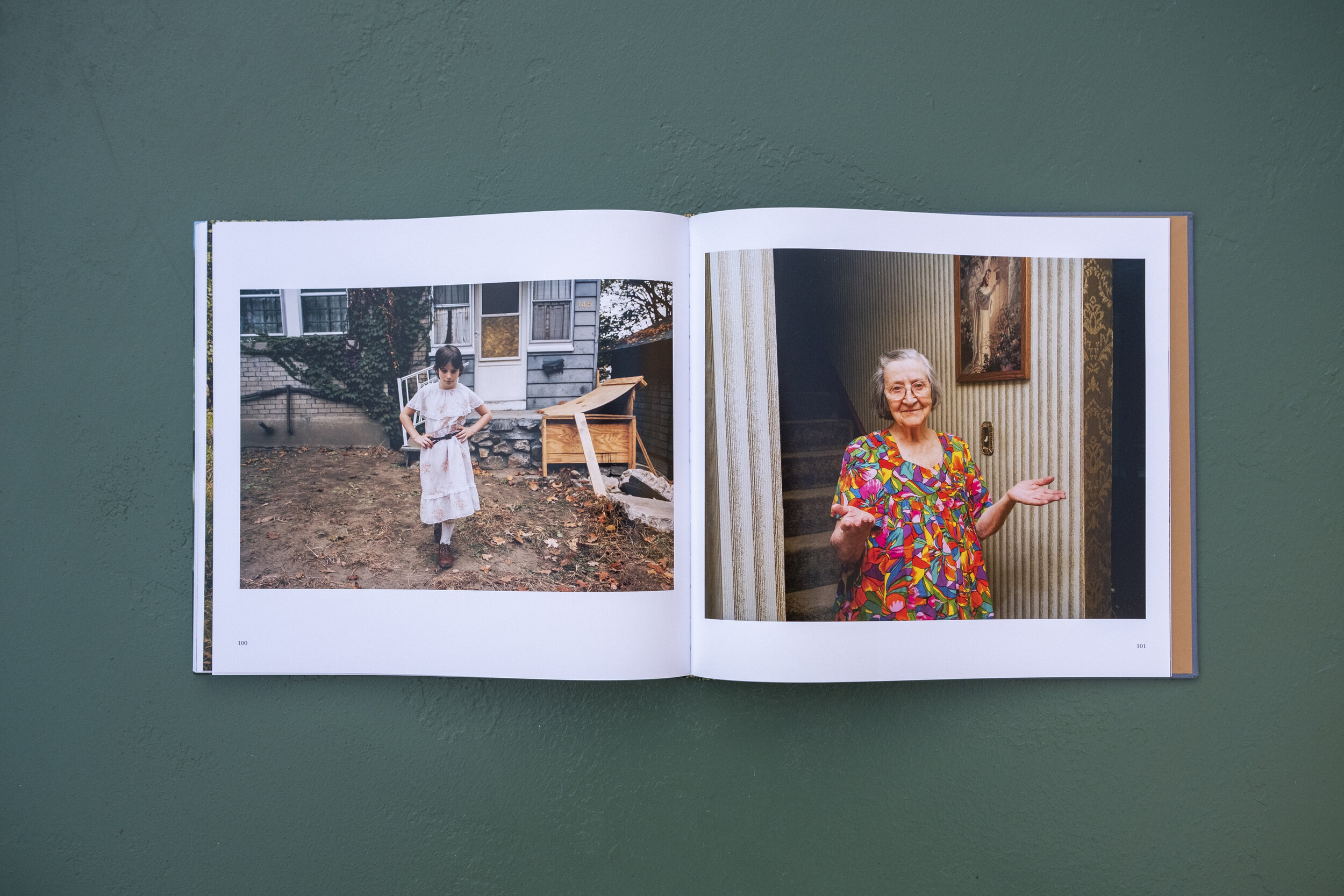

Warning Shots by Mike Smith is not an easy book of pleasing pictures from the quaint, rural South. This is not a book filled with hope of a brighter future, at least not at first glance. It is dark as night.

It’s in this darkness of shadow that we see the first person emerge after a dozen photographs into the book. It’s Smith’s shadow cast onto the first few steps of a home whose lawn is decorated by black lawn-jockeys.

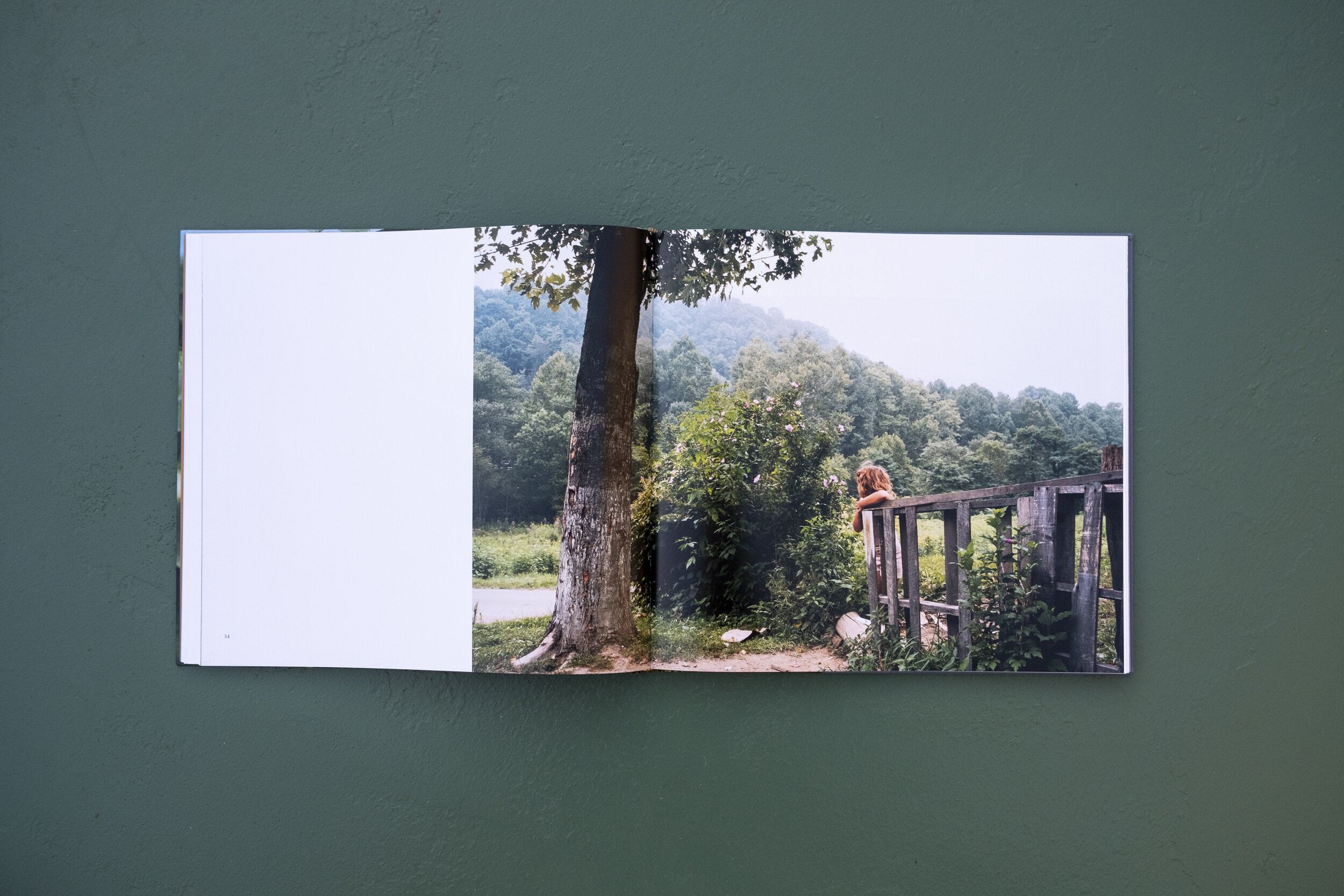

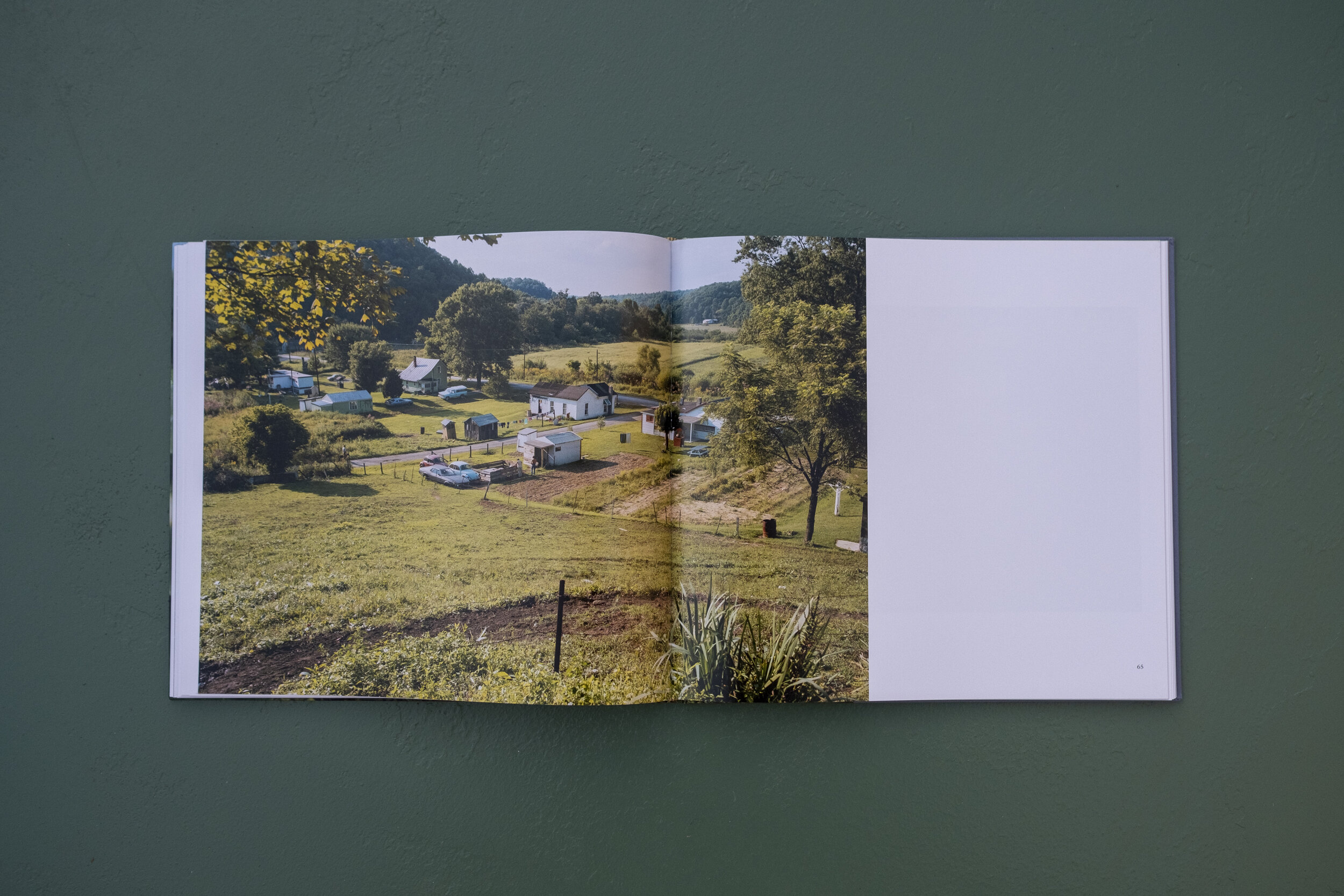

For four decades, Mike Smith has photographed east Tennessee and the surrounding region with the kind of obsession one has that can only be described as love. I don’t mean a first love, or new love, or romantic love. I mean the kind of love that finds its way from your bones to your head and back to your heart. Welty also writes about the notion that you can write (or photograph) from love with straight fury. I sense fury throughout this body of work.

In Diana C. Stoll’s introductory essay, “Shooting in the Dark,” she writes, “These are not quiet or inscrutable metaphors - and maybe that is the point. In these benighted times, guesswork no longer has a place; so Smith lays it all out for us, clear as day.” Stoll couldn’t be more spot on. This book is anything but quiet.

Mike Smith began teaching photography at East Tennessee State University in 1981 and taught there until he retired in 2018. That, in and of itself, is an incredible accomplishment as it seems rare that one works in the same job or with the same company for an entire career. His work there greatly influenced generations of photographers, many of whom would point to Smith as the reason they studied photography and continue to practice.

This work was assembled during the 2016 election cycle. Given the dates the pictures were made, they suggest this climate isn’t as new as we might think, or better yet, think we’ve somehow outgrown. Too often, we don’t think about pictures because we aren’t required to. We are inundated with loaded images. We are spoon-fed pictures. We are lulled into a sugar coma by the ease of pictures that require little of us. This is not that.

Spending time with this book, with these pictures, makes me uncomfortable. I’m glad for it. If it doesn’t make the viewer uncomfortable, doesn’t evoke some visceral response, some reflexive withdrawal, there is something seriously wrong with the viewer. There is no safety, no safety net in these photographs.

The first chains placed on a slave brought from Africa, the first Native American pushed off the land, the first chunk of coal extracted, the first tree felled, this is our evidence and yet we are surprised by it and want nothing more than to look away or suggest something is “wrong” with “those people.” This is our inheritance.

These pictures, while made in Appalachia, represent a far wider reach than rural east Tennessee. In the closing essay, “Troubling Images,” Eric Paddock writes, “As Smith’s photographs penetrate to these sad, alienated and frightening layers of the region’s landscape, we know they lie below the surface in other parts of the country, too."

Images like this convince us we can know a place, point to it, but allow us to miss, perhaps withdraw from the much heavier, more painful work of looking inward, or asking of ourselves what part do we play in this?

*Editorial note: I received a complimentary review copy of Warning Shots from Kehrer Verlag.

Preview Warning Shots here.